| Title | Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate – A geologist wanders through the world of wine |

| Author | Alex Maltman |

| Publisher | Académie du Vin Library |

| Date | 2025 |

| ISBN | 9781917084628 |

| Pages | 304 |

| Summary | Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate is based on 12 feature articles published over the years in the magazine The World of Fine Wine plus six new essays. |

| Excerpt | Académie du Vin Library |

About the Author

Alex Maltman is emeritus professor of Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University in Wales. He has researched and lectured on vineyard geology on four continents and is a seasoned speaker at international conferences. He has contributed to a number of wine books, including The World Atlas of Wine and The Oxford Companion to Wine, for which he is responsible for the geological entries. Alex is the author of the acclaimed book Vineyards, Rocks and Soils: A Wine Lover’s Guide to Geology (Oxford University Press, 2018).

About the Book

Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate is based on 12 feature articles published over the years in the magazine The World of Fine Wine. With the feedback I received on those essays, I judged that they were providing insight into the topics they covered, and readers found their content useful. It struck me, however, that in a magazine they were somewhat ephemeral, and that collecting them in book form could be a useful contribution to the wider wine literature. This book is the resulting anthology, together with six new essays, including the one that follows.

It’s the subtitle, A Geologist Wanders through the World of Wine, that really indicates the book’s nature. The content deals with an eclectic range of topics—the “wandering”—but all seen through the eye of a geologist. I like to think that, unlike my earlier wine book, which was more of a reference manual, this text allows readers to dip in and read, as each chapter is self-contained.

The first chapter outlines some basic ideas of how vines interact with vineyard soils and what this may mean for the wine in our glass. The second chapter recalls the long and little-told story of how we reached our present scientific understanding of photosynthesis. Several chapters discuss the cultural and wine significance of geological materials, such as schist, tuff, granite, flint, and limestone, while some are more concerned with places, such as the Loire Valley. Some approach broader issues, including the matter of metaphors, as in the excerpt provided here. And to underline the wide-ranging nature of the essays in the book, the final chapter examines how geology is handled in the worlds of whiskey and beer. The contrast may be surprising. – Musings on Minerals and Metaphors, GuildSomm

Articles

- Between a rock and a hard place Vineyard Soils – WFW July, 2015

- Granite: Rock of grandeur, rock of ages – WFW October, 2023

- Tuff, tufa, tufo, and tuffeau: A tangled world – WFW August, 2022

- The Diverse Dynasty of Shale, Slate, and Schist – WFW June 2016

- The Loire and its dazzling geology – WFW November, 2024

- Clay: What it is and why it matters – WFW August, 2022

- Limestone: Holy grail or charismatic illusion? – WFW July, 2022

- Five fabled vineyard soils – WFW September 2023

- Flint: A striking story – WFW August, 2022

- Brisk wine from granite but delicate from sand – WFW November 2023

Earlier WFW articles have been re-used in Vineyards, Rocks and Soils

- Wine and the Mists of the Distant Past – WFW June 2015

For all his WFW articles, see

See also

- On rocky ground – Decanter December, 2018

- Musings on Minerals and Metaphors – GuildSomm, June 2025

- Part 1: Soil Principles – GuildSomm, Jan 2013

- Part 2: Vineyard Geology – GuildSomm, Jan 2013

- It’s in the soil: unearthing the truth about rocks and wine flavour – The Wine Society September 2025

Book Reviews

- There’s no taste like stone – Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate: A Geologist Wanders Through the World of Wine by Neal Neal Hulkower, 2025

- Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate, Reflections on geologist, Alex Maltman’s compiled essays by Alice Feiring

- Book Review by David Crossley – Wide World of Wine 2025

- Books: Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate by Alex Maltman by Sophie Thorpe – Decanter July, 2025

Interviews

Articles Summaries

On Rocky Ground

Maltman challenges the new orthodoxy elevating vineyard geology to pre-eminent importance, arguing that while geology determines physical landscape (topography, drainage, water retention), scientific evidence reveals more modest, indirect roles than marketing claims suggest. The critical disconnect: vines construct themselves from atmospheric CO₂/O₂/H₂O via photosynthesis; 14 mineral elements must dissolve in soil pore-water for root absorption, but geological minerals are insoluble—humus is essential as the only natural source of nitrogen and phosphorus, recycling nutrients and supporting soil organisms. Vines actively regulate nutrient uptake (the source is irrelevant); wine contains only ~0.2% tasteless inorganic matter; invisible microclimate variations and microbiology often exceed soil effects, yet lack geology’s “charisma” in marketing. Grand assertions about geology (e.g., “complexity because of slatey para-gneiss”) require explaining how this works—the gap between marketing claims and scientific mechanisms remains unbridged.

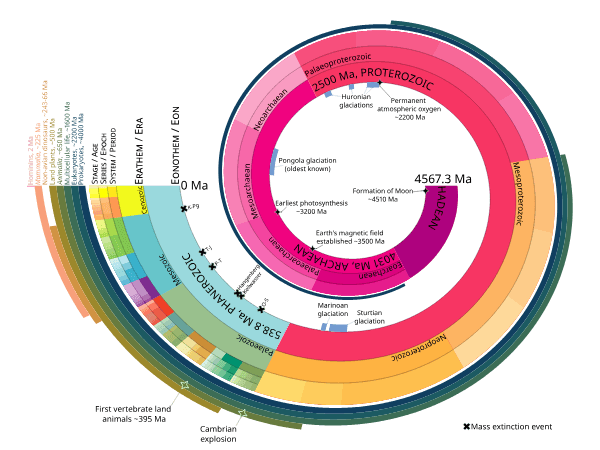

Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Vineyard Soils

This geological primer clarifies fundamental vineyard terminology, addressing widespread confusion in wine literature where rocks, minerals, soils, and stones are routinely conflated. The Earth’s crust comprises just eight dominant elements (oxygen 46%, silicon 28%, plus Al, Fe, Mg, Ca, K, Na) that combine into minerals (rigid compounds), which aggregate into rocks. All minerals except rare examples (opal, amber) are crystalline—meaning “crystalline soils” claims are meaningless since all vineyard soils are inherently crystalline. The article systematically debunks common misconceptions: geological abundance doesn’t equal nutrient availability (Lodi granite contains abundant potassium feldspar yet <2% becomes bioavailable); vines actively regulate nutrient uptake within optimal ranges rather than passively absorbing; nutrient source (dolomite, mica, or fertilizer bags) is irrelevant to vines; “mineral-rich soils” are meaningless (all soils comprise geological minerals); and old vine deep roots access supplementary water in bedrock fissures where minimal weathering means little nutrient availability—bulk nutrition derives from humus-rich upper soil layers.

Musings on Minerals and Metaphors

Maltman categorizes wine-taste metaphors into three types: (1) scientific commonality where flavor compounds exist in both wine and reference (blackcurrant in Cabernet, rotundone in Shiraz/black pepper); (2) useful recollections without direct chemical links (Barolo = forest floor); and (3) creative imagination comparing to things with no flavor or experience—where most “earthy” metaphors fall, requiring mental conjuring of what rocks would taste like. The insolubility principle: slate, talc, graphite, and chalk are wholly insoluble, tasteless, and odorless—roots absorb only dissolved substances, and things must vaporize to smell. “Talc aromas” reference perfumed toiletry not the mineral; “graphite” refers to aromatic cedarwood pencil casings; wet stone “petrichor” comes from organic compounds (bacteria, algae, molds) on any porous surface displaced by raindrops, having nothing to do with geology.

Maltman and student Li-Ming Tan analyzed iodine in Chablis grand cru samples versus Corton Chardonnay and supermarket wines from Mendoza/Barossa—all values minuscule, but lowest from Chablis (despite “fossilized oyster shells give unique iodine flavor” claims) and highest from Barossa. Minerality—the most commonly used wine descriptor today—appeared suddenly decades ago, replacing “steely, lean, austere”; given the blur surrounding the term, science struggles to identify what triggers the sensation. With minerality and similar geological words, “we’re not just comparing—we’re imagining, mentally conjuring what rocks and minerals ought to taste like,” which isn’t wrong but requires recognizing we’re using creative metaphors, not literal connections.

Granite: Rock of Grandeur, Rock of Ages

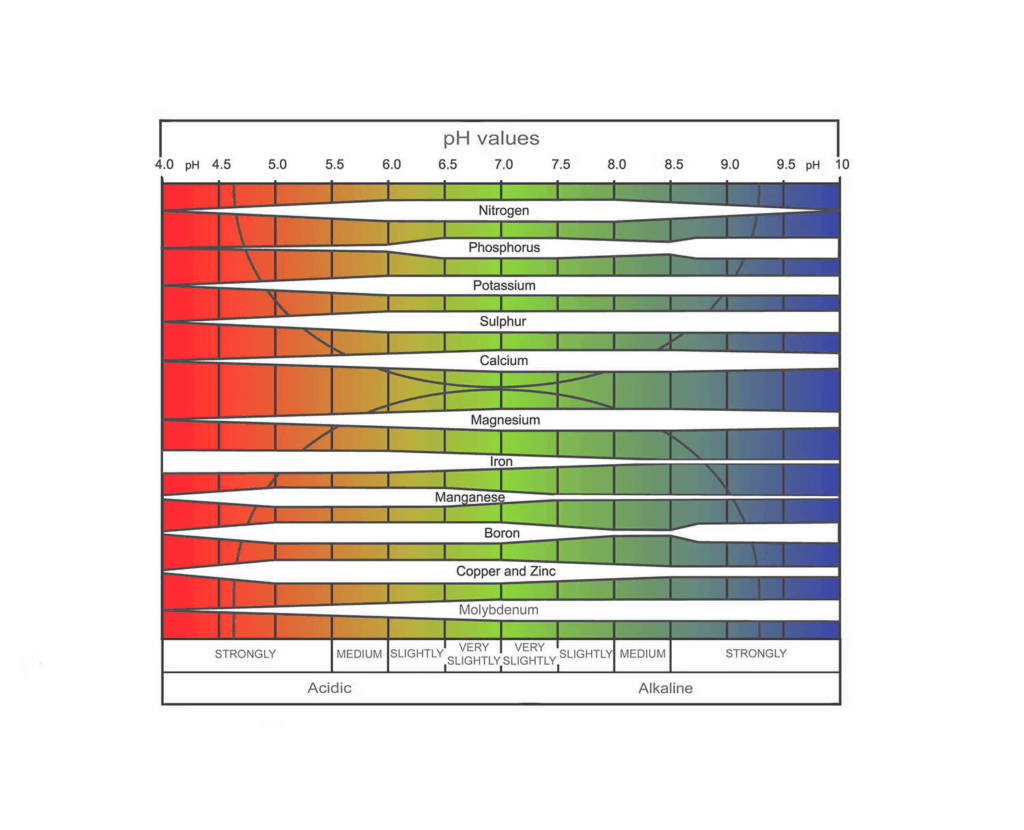

Granite’s celebrated strength and polishability built grand structures (Tower Bridge, Victorian lighthouses, Palacio de San Lorenzo) and provides nearly all world curling stones from Scotland’s Ailsa Craig, yet decays over geological time as potassium feldspar (~40% of granite) reacts with slightly acid water to form kaolin clay, creating soil accumulations thick enough for commercial mining. Two key viticultural features: free drainage from loosely packed quartz particles creating “buried treasure chest” soils, though lack of water retention proves problematic in dry years; and low fertility ideal for concentrated fruit, though granite’s absence of calcium carbonate creates acid soils restricting magnesium/phosphorus availability, requiring lime addition in places like Darling, Paarl, and Stellenbosch. Granite soils are typically potassium-rich, but >90% is locked in unweathered feldspar (only <2% accessible in Lodi soils)—excess uptake reacts with tartaric acid forming insoluble “wine diamonds” (potassium tartrate crystals), lowering acidity and producing flabby, unstable wines.

Common claims that Gamay and Syrah “prefer” granite reflect classic European sites, not universal truth—both flourish in other soils within Beaujolais and Rhône; Syrah thrives in non-granite Barossa, Hawke’s Bay, and Yakima Valley. Wine character claims are utterly contradictory: whites described as both “tight, edgy, accessible young” and “substance, breadth, longevity”; “opulent tropical pineapple” versus “mineral, edgy salinity”; reds as “bass notes, power, viscosity” or “floral, fragrant, high tension”. Literal tasting claims (“you can really taste the granite”) are creative metaphors—granite is famously insoluble and cannot be tasted literally; it has identical mineral composition to other rocks (shale, schist) in different proportions with “remarkably similar” chemical analyses, meaning no special granite ingredient exists.

Tuff, Tufa, Tufo, and Tuffeau: A Tangled World

The confusion stems from Roman tophus encompassing two geologically different materials: volcanic tuff and spring-precipitated tufa, with the word transmuting into local vernaculars as building stones spread across the empire. Since the 1800s, geologists systematically restrict tuff to volcanic silicate rocks (fine ash/ejectimenta <2mm discharged from volcanoes) and tufa to calcareous rocks (calcium carbonate limestone) formed by cold groundwater precipitation—but popular wine writing still conflates them despite creating opposite soil conditions (tuff yields acidic, potentially fertile soils; tufa yields alkaline soils with nutrient restrictions above pH 7.5). Examples of ongoing confusion: Piemonte’s calcareous sedimentary cellars incorrectly called “tuff”; Hungary’s Eger volcanic tuff cellars with visible jagged fragments called “tufa” in prominent materials; Vignanello wines on siliceous Vico volcano tuff described as growing in “tufa”; Orvieto’s tuff caves called “tuffeau” (Loire’s sandy limestone).

Additional terms: hornfels (heat-altered metamorphic rock near granite intrusions; named from Saxon miners’ “horn stone” for splintery appearance); travertine (hot-water calcareous precipitate denser than tufa, used for Rome’s Coliseum—100,000 tons—St Peter’s Basilica, and modern McDonald’s façades, though geologists debate where to “draw the line” with tufa based on water temperature); and tuffeau (French sedimentary sandy limestone in Anjou/Touraine, built Loire châteaux like Chambord and Blois, stratified from submarine debris accumulation, not a chemical precipitate despite sounding like tufa). Unless readers have prior knowledge, descriptions like “soils consist of tufa” or “grown on tuff” don’t guarantee actual geological composition or wine character.

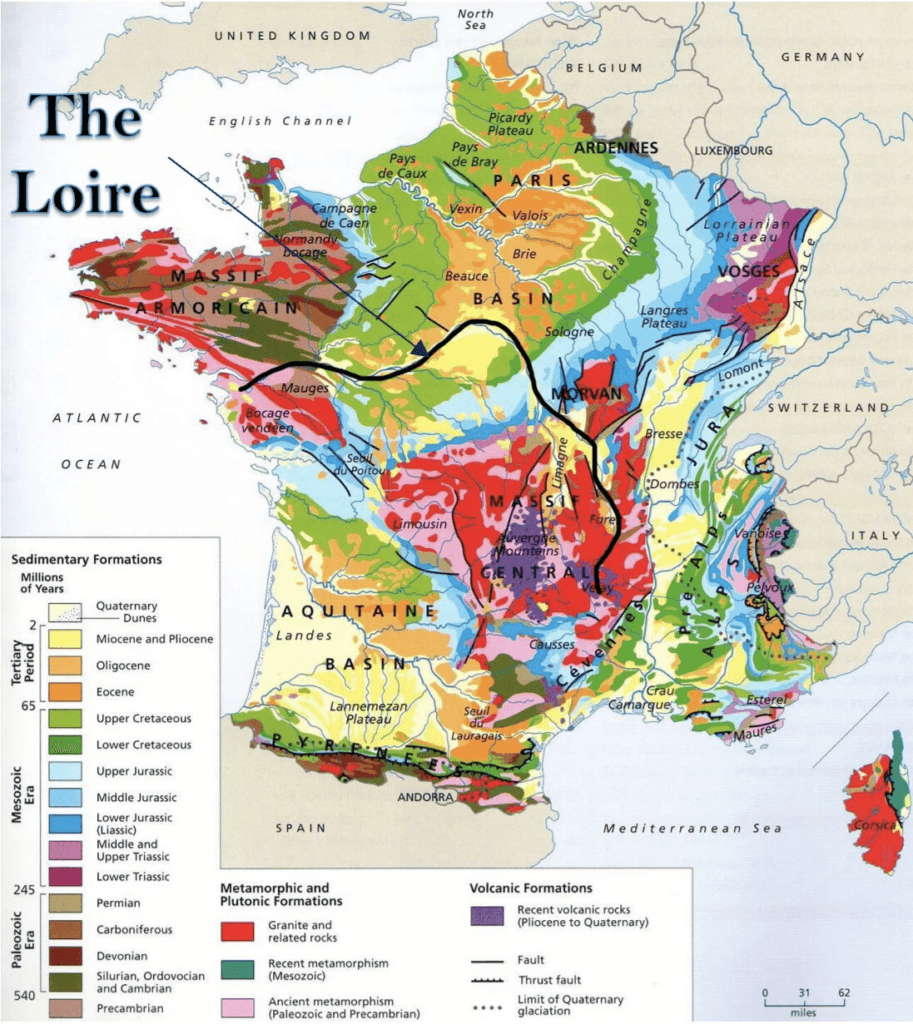

The Loire and Its Dazzling Geology

The Loire springs from Mont Gerbier de Jonc (Cévennes), a phonolite volcanic hill where rainwater percolates through fissures, meets crystalline basement rocks, and emerges as springs that coalesce into the river, which initially flows southward before swinging northward due to Massif Central uplift forces. The river progresses through diverse geological formations: Côtes du Forez granitic bedrock with basalt patches promoted as “Loire Volcanique”; Paris Basin sedimentary strata (Middle Jurassic through Tertiary) deposited when the Atlantic formed and seawater flooded the region; Sancerre and Pouilly where geological faults displaced Cretaceous bedrock downward, but tougher flinty rocks resisted erosion to form higher land including Sancerre’s prominent butte. Touraine’s Azay-le-Rideau shows geology ranked “rather weak” in vineyard influence factors, yet the illustrious tuffeau blanc limestone used for Loire châteaux (Azay-le-Rideau, Chambord, Blois) became inextricably linked with regional wine image despite vineyard area shrinking to one-tenth its 1883 extent.

Anjou’s bisected geology transitions from pale tuffeau (L’Anjou Blanc) to crystalline basement (L’Anjou Noir) near Angers, where historic black slate roofs (produced since the 6th century until tragic 2014 mine closure) enabled elaborate château turrets; roof repairs now require Spanish Galician slates. Savennières’ “paint box” soils include rhyolite, spilite (submarine basalt), hyaloclastite (basalt-sediment mixtures), white quartz, red jasper, deep blue-black phtanite (black chert), Angers slate (Ordovician, ~450 million years), and older schist (Brioverian, >550 million years)—wine claims cite schist bringing “seriousness,” quartz creating “acidity,” and phtanite conveying “mystical complex aromas,” but without explaining mechanisms. Muscadet’s 1799 earthquake (strongest ever locally, sixth in France) reflects major geological faults juxtaposing granite (Clisson cru) with gabbro (Gorges, Le Pallet); serpentinite (magnesium-rich, typically creating “barrens” hostile to plants) caps Butte de la Roche in Goulaine cru, where vines manage via Couderc 3309 rootstock producing concentrated fruit from stressed conditions.

Clay: What It Is and Why It Matters

Clay’s two fundamental properties—stacked silicon-oxygen sheets bonded by intervening elements (like a multi-deck sandwich) and microscopic size (0.002mm flakes, one-hundredth thickness of human hair, invisible to naked eye)—explain its unique behaviors including malleability, soil drainage clogging, and variable bonding strength between different clay types. Kaolin consists of relatively large, rigid flakes with simple chemistry (aluminum, silicon, oxygen, hydroxide) and strong bonding, forming where water reacts with granite’s feldspar; it produces thin, strong, translucent porcelain when fired (discovered in 1712 by Jesuit missionary in China, spurring European search leading to surgeon Jean-Baptiste Darnet’s 1700s discovery in St-Yrieix, France). Vineyard examples include Temecula Valley, Rías Baixas, Dão, and South Africa’s Western Cape (Darling, Paarl, Stellenbosch) where soils reach acidic pH <4, requiring lime addition; high potassium content reacts with tartaric acid forming “wine diamonds” (potassium tartrate), lowering acidity and producing flabby wines; nano-kaolin sunscreen sprays now block UV radiation, reduce sunburn damage (15% crop loss in Queensland’s Granite Belt), increase light reflectance, improve ripening, repel insect pests, and optimize water use.

Montmorillonite (smectite) flakes are vastly smaller (little more than a millionth of a millimeter thick, 50× smaller than Ebola virus), with 1 gram containing surface area greater than two parking spaces, exposing countless loosely-held nutrient atoms (calcium, magnesium, iron)—the fundamental source of vine nutrients. Water seeps between sheets, prising them apart and storing substantial amounts, benefiting free-draining/drought-prone vineyards (Pomerol’s argile bleue for Petrus, Trotanoy, Le Pin; Jordan’s Mafraq region; Romania’s Dealul Mare), but “shrink-swell” behavior creates severe challenges: sodium montmorillonite expands to several times original size, creating sticky masses blocking drainage and causing surface waterlogging; upon drying, it shrinks and cracks, increasing density, hindering roots, causing premature ripening. Foundation damage from “heave and subsidence” (repeated lifting/settling cycles) exceeds flooding losses in France, tornadoes/earthquakes/hurricanes combined in the US, and constitutes the UK’s single biggest annual building damage insurance claim (£500 million); climate change is worsening the problem. Bentonite (montmorillonite’s commercial form) is mined globally (2+ million tons, ~$2 billion value) primarily for wine clarification/fining, though it removes desirable aromatics and UC Davis studies showed it strips aluminum into wine, raising contamination concerns; it’s crucial for vegan wine production, replacing animal-derived fining agents.

Limestone: Holy Grail or Charismatic Illusion?

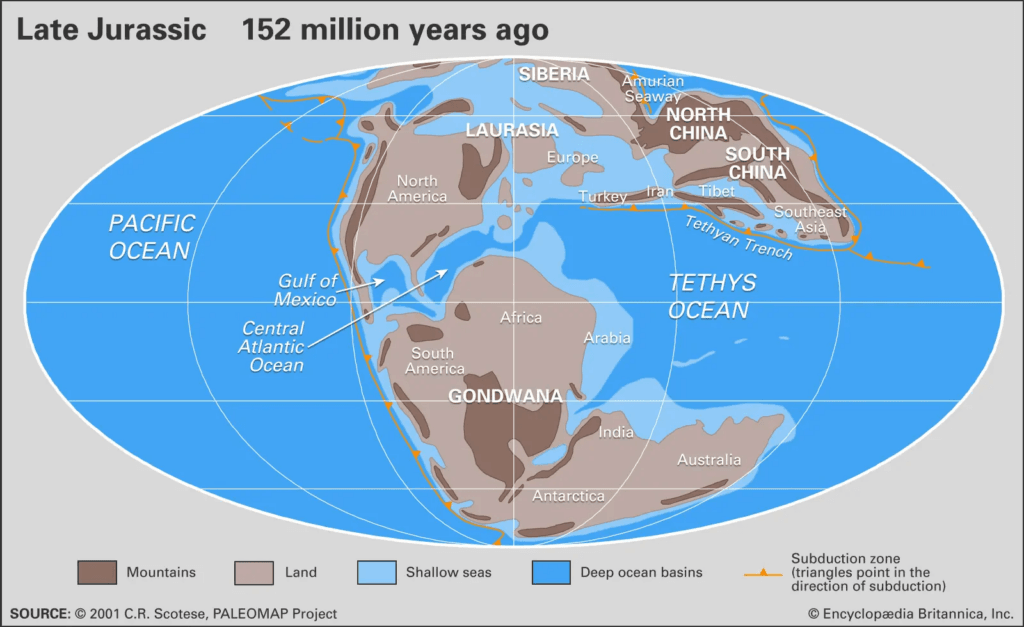

The ancient Tethys Ocean‘s shallow western reaches fostered abundant marine life whose calcium carbonate shells created thick calcareous deposits that hardened into limestone, thrust upward to create land where Vitis vinifera originated and spread—approximately half of France, one-third of Italy and Spain are underlain by limestone, making calcareous soils prominent in the original Eurasian grapevine milieu and almost inevitably involved when certain areas were identified as producing superior wines. Limestone is compositionally different from most rocks: pure calcium carbonate (carbon and oxygen, not silicon) that dissolves relatively easily and weathers to alkaline soils (pH ≥7), creating distinctive landscape features (Enchanted City near Cuenca, Cassis cliffs, Alps/Jura escarpments) and world-famous caves (Reims, St-Émilion, Moldova’s 150-mile Mileștii Mici tunnels). The “sweet earth” produces optimal nutrient availability at pH ~6.5 (calcium interacts with clay to create spaces promoting warmth, drainage, root penetration, and microbial diversity), but purer limestone soils dominated by calcite present serious problems as pH increases beyond 7: boron availability declines, zinc becomes deficient (>50% of Montalcino soils lack accessible boron and zinc causing leaf shriveling and millerandage), and most critically, iron becomes locked in insoluble compounds—a one-unit pH increase decreases iron solubility a thousandfold, causing chlorosis (yellowing leaves).

The phylloxera catastrophe revealed limestone’s fundamental challenge: Vitis vinifera evolved on Tethyan calcareous deposits and developed mechanisms to combat chlorosis by pumping hydrogen and organic acids from roots to increase soil acidity and release iron, but North American Vitis species evolved on acidic gneiss and granite soils alongside phylloxera, developing biochemical defenses vinifera never acquired. In 1887, botanist Pierre Viala was sent to find American vines tolerant of limestone soils, eventually discovering Vitis berlandieri thriving on Texas Hill Country limestone at Dog Ridge, but cuttings proved reluctant to root, requiring selective crossings; the famous 41B rootstock (berlandieri × Chasselas) rescued Charente vineyards and is used for >80% of Champagne vines, yet chlorosis challenges persist because North American varieties generally dislike high-pH limestone soils. Wine character claims are highly inconsistent: even in Burgundy’s Côte d’Or, some writers describe limestone wines as “big, strapping” with “unmatched opulence” contradicting the “liveliness, edge, nervousness, finesse” narrative; wines from Germany, Austria, and Hungary attract similar “finesse” descriptions but come from acidic, non-calcareous soils; wines from limestone in warmer climates (Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley) are not noticeably acidic. A Dutch experiment growing three cultivars in different soils (including limestone) with uniform vinification found trained tasters could not detect significant differences attributable to soils, though they did detect variations from different yeasts; regional examples further confound the narrative (St-Chinian’s limestone yields fuller wines while schist produces acidity/tension/elegance—opposite of northern France’s pattern).

Five Fabled Vineyard Soils

Kimmeridgian of Chablis: “Kimmeridgian” denotes a geological time period, not rock type—southwestern UK’s Kimmeridge has oilfields; Canada’s Kirkland Lake has diamond-bearing rocks; Turkey has granites; California has igneous rocks, all Kimmeridgian—yet none are at Chablis. Geologists argued about the definition for 200+ years, reaching international agreement only in 2021 based on specific ammonite fossils not present at Chablis; grapevines don’t care about geological age (physical/chemical properties matter), and the phrase “Kimmeridgian soil” refers to bedrock while vines grow in vastly younger soil above it—in temperate glaciated zones, soils are only thousands of years old and still forming; at Chablis, soil creeps downslope, requiring centuries of growers carting accumulated debris back uphill, creating mixed mid-slope viticultural soils.

Albarizas of Sherry: Microfossil-rich marls (diatoms, radiolaria, foraminifera) from ancient seas 20 million years ago, now weathering into soils with exceptional water-holding capacity (absorbing one-third volume like a sponge) crucial during arid growing seasons; varied subtypes (tosca de barajuelas richest in diatoms with leafy structure encouraging sideways roots; tosca cerada most calcareous, soft when wet but baked when dry; tosca lentejuelas “sequins,” foraminifera-rich encouraging deeper roots for lighter wines) may influence yeast strains (softer albarizas encourage vigorous beticus, denser soils favor gentler montuliensis, both intrinsic to Sherry’s flor).

Rutherford Dust: Origin unknown (attributed to Maynard Amerine or André Tchelistcheff’s “it takes Rutherford dust to make great Cabernet”), but Rutherford AVA soil—alluvial gravels, loams, sands, silts—is far from dusty (dust is airborne fine material); the Rutherford Bench is an alluvial fan providing suitably low fertility and superb drainage with vine roots probing 20+ feet, benefiting from Napa warmth tempered by San Francisco Bay maritime air and significant diurnal temperature variation. Meaning utterly blurred: some believe it literally means soil, others think “terroir” broadly, but most commonly refers to wine characteristics—especially mouthfeel (“granular or dusty tannins coupled with cocoa powder”), since research shows restricted water provision from these soils importantly develops grape tannins; the Rutherford Dust Society: “dust evokes in four simple letters a specific place and complex flavors”; Andy Beckstoffer: Tchelistcheff “did not mean they had to taste of dust… needed to taste like they came from Rutherford’s vineyards”.

Terra Rossa of Coonawarra: Over 500,000 years, fluctuating sea levels created coastal reefs and dunes; wind-blown calcareous clayey silt on porous limestone filled surface hollows, creating the Coonawarra ridge meters higher than surrounding damp land; drainage and aeration leached calcium, leaving insoluble hematite-reddened clays providing restrained fertility and water storage enhanced by underlying fissured limestone; slight elevation raises air dryness and sunlight exposure, producing smaller, more intensely colored Cabernet grapes with well-ripened phenols yielding characteristic blackcurrant and minty wines; wine color comes from anthocyanin pigments in grape skins, not from soil redness despite writer assertions.

Gimblett Gravels: Free-draining riverbed pebbles left high and dry after 1867 flooding (15 inches rain in 10 days) caused the Ngaruroro River to completely change position; barren shingle couldn’t sustain sheep grazing year after year until 1981 when CJ Pask realized inland areas were warmer and planted Cabernets that attracted acclaim; growers organized, applied for registered trademark (not official appellation), precisely defined limits, laid down strict quality requirements; essentially hydroponic viticulture—just enough topsoil provides humus-borne nitrogen/phosphorus/sulfur, but all other nutrients come from irrigation waters rising among Taupo volcano deposits and passing through graywacke, easily dissolving sufficient nutrients; viticulture impossible without irrigation (vines fail if rodents chew pipes), yet Gimblett Gravels wines are cited as outstanding terroir-driven examples despite grapevines’ vital water and nutrient supply coming from far away.

Flint: A Striking Story

Flint is silicon dioxide (silica) with extremely fine crystals (20,000th of a millimeter across), distinguishing it from larger-crystal silica minerals like quartz; its efficient three-dimensional silicon-oxygen lattice makes flint hard, tough, chemically inert, and virtually insoluble, rendering it odorless and tasteless—raising immediate problems about what “flinty” wine actually means. Flint forms from decayed silica skeletons of ocean organisms (diatoms, radiolaria) that accumulated on sea floors 90 million years ago during the Cretaceous period, with optimal conditions in what is now eastern England and north-central France, producing the world’s best flint around Norfolk’s Grimes Graves and France’s Le Grand Pressigny; famous wine associations include Champagne’s Côte des Blancs and Côte de Sézanne, Loire’s Vouvray, and especially Pouilly and Sancerre, though ironically flint soils account for only 20% of these appellations (most occur at St-Satur, Ménétréol, Thauvenay, St-Andelain, Tracy). Flint provides good drainage and restricts nutrients for meager soils yielding finer grapes, but this results from pebbles existing, not from being flint specifically; claims that flint pebbles absorb daytime heat and radiate warmth at night apply equally to all rock types with minimal practical benefit; disadvantages include flint’s hardness and sharp edges damaging farm machinery (broken harrows, twisted mower blades, punctured tires), and steel striking flint creates sparks that can ignite fires in dry conditions (water buckets scattered throughout Domaine de la Chezatte in Sancerre).

Despite being among the most common wine descriptors, “flint,” “flinty,” and “gunflint” lack precision upon examination, appearing across diverse wines—not just acidic cool-climate whites but also rich reds (Cayuse Grenache, Chave Hermitage, Priorat), sweet wines (Château Guiraud, Barsac), whisky, and even cheese. Three explanations for what “flinty” might reference:

- (1) Edge and angularity: flint’s conchoidal (shell-like curved) fracture pattern produces sharp edges and points because its framework lacks internal weaknesses; descriptions like “chiseled and flinty,” “flint edge that seems angular” likely allude subliminally to this physical property.

- (2) The smell of abrading flint: Swiss researchers studying toilet odors accidentally isolated hydrogen disulfane (HSSH)—a compound with “flint-like odor, similar to a dentist drilling teeth”—produced when flint surfaces containing sulfur impurities are rubbed together in air; wine professionals judged Swiss Chasselas wines highest in HSSH as most “flinty”; another sulfur compound, benzenemethanethiol, detectable at 0.3 parts per trillion and measured over 10 parts per trillion in some Loire Sauvignon Blancs, also correlates with flinty aromas; however, these compounds aren’t present in grapes but generated during yeast fermentation, meaning there’s no direct connection to vineyard flint.

- (3) Gunflint and smoke: despite popular belief, flint cannot spark—it’s the steel that sparks when struck against hard flint, and the distinctive smell is burning steel, not flint; true triboluminescence (light from breaking chemical bonds when flints strike together) produces no heat or smell; the “gunflint” aroma likely references burning steel sparks, though the author questions how many modern wine tasters have actually experienced striking flint-on-steel or smelled antique gunfire, where burning gunpowder overwhelms any spark odor; “gunflint” descriptors blur into “smoky” and “struck-match” themes, probably involving imagination about what gunflint should smell like.

Brisk Wine from Granite but Delicate from Sand

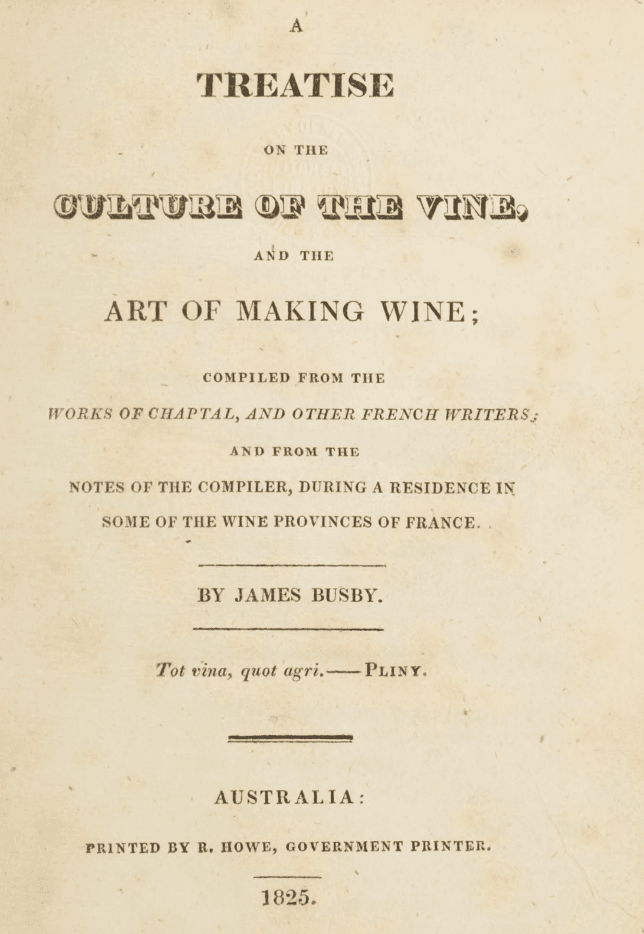

James Busby, often called the “father” of Australian wine and a founder of New Zealand, is buried in London’s Anerley suburb after a troubled life in which he “never really settled or made friends,” yet his 1820s vineyard manuals inspired English-speaking wine industries and are still cited today—a 2018 terroir book devotes almost a page to his words, usually supporting beliefs that geology can be tasted in wine. Busby’s 1825 Treatise on the Culture of the Vine (published one year after arriving in Australia aged 23, based solely on a single visit to parts of Bordeaux and reading French texts) carefully argued that “intrinsic nature of the soil is of less importance than that it should be porous, free and light”—pebbly, calcareous, volcanic, and granitic soils all have appropriate physical properties while clay is too cold and firm. Then came the anomaly: in a single paragraph, completely out of the blue and contradicting all surrounding text, Busby declared without expansion or explanation: “The sandy soil will, in general, produce a delicate wine, the calcareous soil a spirituous wine, the decomposed granite a brisk wine”—this single cryptic sentence is the basis for most modern citations claiming Busby supports geology-to-taste connections, yet he offers no rationale for how this might occur (presumably based on anecdote from France); his claim that calcareous soils yield “spirituous” (high alcohol) wine contradicts his own Champagne example where calcareous soils don’t produce high alcohol.

Busby’s 1830 Manual of Plain Directions for “smaller settlers” introduced but then rejected the idea that deep subsoil/bedrock affects wine—”I question whether, were it ever so well ascertained, we could derive much advantage from the knowledge of it”—and that oft-quoted sentence about wine traits varying with soil was absent from this version. After a four-month 1831 European tour, Busby’s 1833 Journal shows radically changed views: new conviction that calcareous soils are supreme for quality dry wines (struck by Jerez’s finest wines from calcareous albariza, Burgundy’s Côte d’Or higher calcareous vineyards, and an unplanned Hermitage visit where a proprietor claimed a “belt of calcareous soil” crossing the granitic hill produced superior wine); Busby—with no training and virtually no hands-on viticulture or geology experience—declared that Jean-Antoine Chaptal (Napoleon’s former interior minister, France’s preeminent chemistry and agriculture expert) and other eminent French writers had been “misled” and “deceived,” pronouncing “Hermitage owes its superiority only to calcareous matter; but for this, the wine would never have been heard of beyond the neighbourhood”. Then he contradicted this too: after proclaiming calcareous soil supremacy, Busby played down soil importance, detailing how excellence comes from careful vineyard management, optimal harvesting, and vinification—”there is more of quackery than of truth” in claims about soil uniqueness, which was “evidently the interest” of producers wanting “excellence imputed to a peculiarity in the soil, rather than to a system of management which others might imitate”. The celebrated “Busby’s vineyard” at Kirkton (Hunter Valley) was actually planted and operated by William Kelman (Busby’s brother-in-law) in 1828; father John Busby (not James) owned the land and died there; James considered Kirkton unsuitable (“I think it unlikely that his wine will ever be above the Vin Ordinaire”), and no record exists of James Busby ever visiting Kirkton, let alone working vines or making wine anywhere—yet the site is now a “pilgrimage” destination, enhancing Busby’s gravitas despite the vineyard being pulled up, house demolished, with only a weathering grave slab remaining among rough pasture.

See also

Comments

One response to “Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate – Alex Maltman (2025)”

[…] Taste the Limestone, Smell the Slate – Alex Maltman (2025) Alex Maltman presents Soil, Vines & the Taste of Wine – The WEC: Wine Education Council, June 2023 […]